In the early 1990s Jerry Stoller coined the phrase, "The language of the plant".

Jerry said that while there are differences in how different plants express themselves, the difference is only a matter of degree.

In order to understand the language, we need to observe how plants (in this case trees) grow. Here is what Jerry Stoller said about trees.

We all like to see healthy and vigorously growing trees and vines. We assume that top growth represents root growth. Vigour of the growth represents vigour of the roots. Vigour normally comes from a liberal use of nitrogen.

As we make closer observations, a different story appears in our mind. Vigorous shoot growth can lead to physiological disorders in our fruit: •Less sugar •Less solids •Poorer shelf-life

Poorer storage life •More fruit disorders

More disease (both bacterial and fungus).

As the trees become older, these potential problems increase.

The older trees have more top growth and dry matter. We have learned to reduce these problems by the art of pruning. In addition, we have learned to cope with these problem by reducing nitrogen application rates.

Pruning is very expensive. If we could reduce this cost, it would save us a lot of money and lower production cost.

When we reduce nitrogen rates, we may reduce yield potential. If we could increase nitrogen use and increase yields, it would lower production cost per unit.

Of course, with our present state of knowledge, the above is not practical.

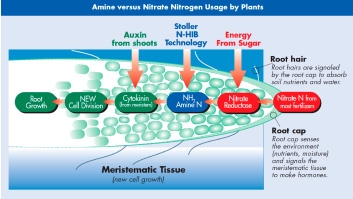

Nitrogen appears to be the problem. Not only does it cause vigorous growth, it changes the hormone balance in the tree —it increases auxins and IAA. It also has the potential to increase ethylene.

When we talk about nitrogen, we are primarily referring to nitrate forms, which supply 80% to 95% of the nitrogen to the crop.

Learning the language of trees

While we observe the top growth, let's go underground and observe the root growth.

Roots grow on carbon compounds (sugars) that are supplied by the leaves. When leaves (shoots) are vigorously growing, root growth activity virtually ceases. When shoot growth slows down, tree roots again begin vigorous growth.

Root hairs grow behind the 'root caps'. This is where they make new tissue for root growth.

Most water and nutrients are absorbed in a 10 mm area immediately behind the root cap.

The old roots are not of much value for absorption of water and nutrients. If new roots do not continue to grow, in about 7 to 14 days they are not very functional for nutrient and water absorption.

Roots do more than just provide water and nutrients. They provide certain hormones such as cytokinins, which are needed to balance other hormones.

When roots become, dysfunctional, the hormone balance affects the tree or vine much more quickly than water or nutrient supply.

Roots start growing when the soil warms. They grow from carbon compounds, which entered the roots from the leaves after fruit harvest.

When the plants begin vigorous shoot growth, root growth slows down. After shoot growth slows down, sugars are again translocated to the roots. The root growth starts to increase.

After harvest, root growth again becomes dominate. This continues until the soil temperature turns cold.

We now understand that the more vigorous the shoot growth and the longer time that we have shoot growth, the more negatively our root growth is affected—this is the key to understanding the language of the tree and vine.

Continues next month

Stoller Australia Pty Ltd phone 1800 FERTILISER www.stoller.com.au

See Tree Fruit November 2014